-

在线学习设计(三):Affordances of the Net

普通类 -

- 支持

- 批判

- 提问

- 解释

- 补充

- 删除

-

-

Affordances of the Net

Effective educational theory must address the affordances and the limitations of the context for which it is designed (Norman, 1999). The World Wide Web is a multifaceted technology that provides a large set of communication and information management tools that can be harnessed for effective education provision. It also suffers from a set of constraints that are briefly outlined in this section.

Online learning, as a subset of all distance education, has always been concerned with providing access to educational experience that is at least more flexible in time and in space than campusbased education. Access to the Web is now nearly ubiquitous in developed countries. The Wall Street Journal of February 4, 2002, reported that 54% of U.S. adults use the Web on a regular basis, and 90% of 15-17 years olds are regular Web users. This high percentage of users would probably include well over 90% of those citizens interested in taking a formal education course. Access to the Web is primarily through home or workplace machines, but placements in public libraries and Internet cafes and connections through personal wireless devices are such that access poses no problems for the vast majority of citizens of developed countries. I have also been surprised by the availability of access in developing countries, as exemplified by free use of the Net in McDonald’s restaurants in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and the numerous Internet cafés, in most Chinese cities. Access is still problematic for those with a variety of physical handicaps; however, in comparison with books or video media, the Web provides much greater quality and quantity of access to nearly all citizens, with or without physical disabilities

Access is increasing, not only to technology, but also to an evergrowing body of content. The number of scholarly journals (see http://www.e-journals.org), educational objects (see http://www. merlot.org/Home.po), educational discussion lists (see http://www .kovacs.com/directory), courses (see http://courses.telecampus.edu/ subjects/index.cfm), and general references to millions of pages of commercial, educational, and cultural content (see http://www .google.com) is large and increasing at an exponential rate. Thus, online learning theory must acknowledge the change from an era of shortage and restrictions in content to one in which content resources are so large that filtering and reducing choice is as important as providing sufficient content.

The Web is quickly changing from a context defined by textbased content and interactions to one in which all forms of media are supported. Much of the early work on the instructional use of the Internet (Harasim, 1989; Feenberg, 1989) assumed that asynchronous text-based interaction defined the medium. Techniques were developed to maximize interaction using this relatively lean medium. We are now entering an era where streaming video, video and audio conferencing, and virtual worlds are readily available for educational use. Thus, online learning theory needs to help educators to decide which of the many technological options is best suited for their application.

The Web’s in-built capacity for hyperlinking has been compared to the way in which human knowledge is stored in mental schema and to the subsequent development of mental structures (Jonassen, 1992). Further, the capacity for students to create their own learning paths through content that is formatted with hypertext links is congruent with constructivist instructional design theory that stresses individual discovery and construction of knowledge (Jonassen, 1991).

Finally, the growing ease with which content can be updated and revised (both manually and through use of autonomous agent technology) is making online learning content much more responsive and potentially more current than content developed for other media. The explosion of Web “blogs” (Notess, 2002) and userfriendly course-content management systems, built into Web delivery systems such as WebCT or Blackboard, is creating an environment in which teachers and learners can very create and update their course content without the aid of programmers or designers. Naturally, this ease of creation and revision leads to potential for error and lessthan-professional-standard output; however, educators who are anxious to retain control of their educational content and context welcome this openness and freedom.

Education is not only about access to content, however. The greatest affordance of the Web for educational use is the profound and multifaceted increase in communication and interaction capability that it provides. The next section discusses this affordance in greater detail.

-

Online Learning and the Semantic Web

We are entering an era in which the Web is changing from a medium to display content, to one in which content is endowed with semantic meaning (Berners-Lee, 1999). If the format and structure of content is described in formalized and machine-readable languages, then it can be searched and acted upon, not only by humans but also by computer programs commonly known as autonomous agents. This new capacity has been most prominently championed by the original designer of the Web, Tim Berners-Lee, and is named by him the “Semantic Web.”

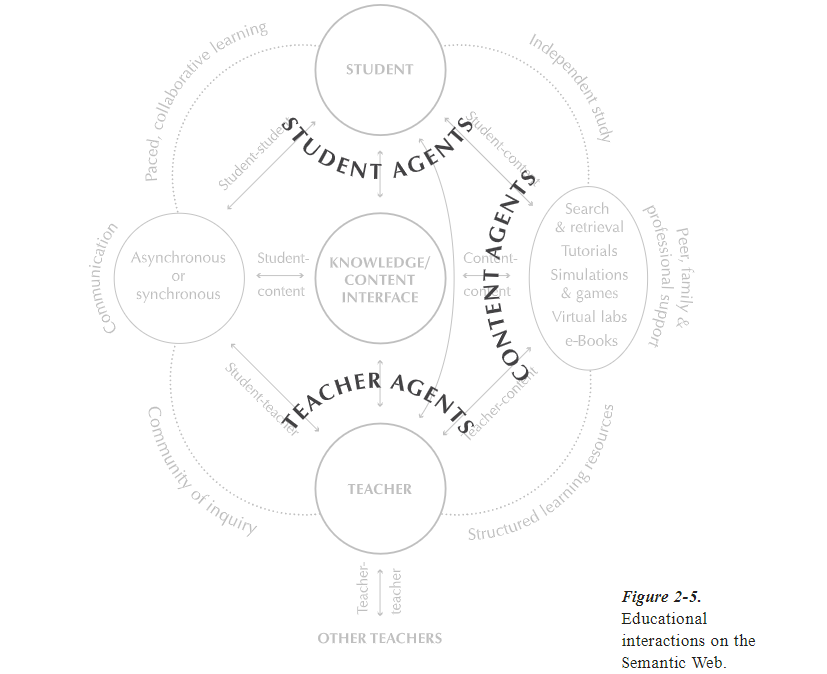

The Semantic Web will be populated by a variety of autonomous agents—small computer programs designed to navigate the Web, searching for particular information and then acting on that information in support of their assigned task. In education, student agents will be used for intelligent searching of relevant content, and as secretaries for booking and arranging for collaborative meetings, for reminding students of deadlines, and for negotiating with the agents of other students for assistance, collaboration, or socialization. Teacher agents will be used to provide remedial tuition, and to assist with record keeping, with monitoring student progress, and even with marking and responding to student communications. Content itself can be augmented with agents that control rights to its use, automatically update it, and track the means by which the content is used by students (Thaiupathump,Bourne,&Campbell, 1999; Shaw, Johnson,&Ganeshan, 1999).

The Semantic Web also supports the reuse and adaptation of content by supporting the construction, distribution, and dissemination of digitized content that is formatted and formally described (Wiley, 2000; Downes, 2000). The recent emergence of educational modeling languages (Koper, 2001) allows educators to describe, in a language accessible on the Web, not only the content but also the activities and context or environment of learning experiences. Together these capabilities afforded by the Semantic Web allow us to envision an e-learning environment that is rich with student-student, student-content, and student-teacher interactions that are affordable, reusable, and facilitated by active agents (see Figure 2-5, below).

-

思考:社会网络、知识网络与社会知识网络的技术支持以及所能提供的学习服务

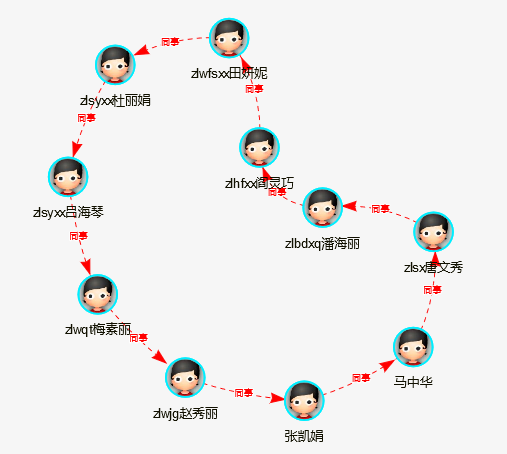

社会网络学习场景:

在学习的过程中,你可以查看基于某个主题的全体参与者(头像)

你可以点击每一个学习者头像,进入其学习空间查看她的简历,学习轨迹与路径,学习爱好以及好友圈子;

你可以通过点击用户头像的方式,和她/他建立社交关系,可以发送消息,邮件,可以微信或者QQ。

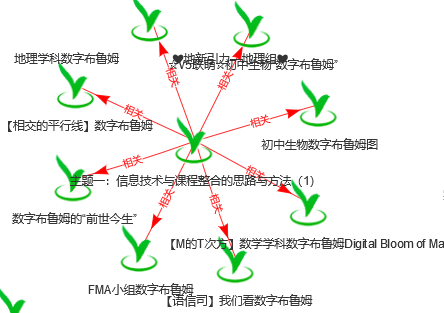

知识网络学习场景:

-

课前可以给学生展示基于某一个主题的全部知识框架;

课中可以帮助学习者进行知识的梳理与观点的联结,学习者可以在学习的过程中能够创建某一个知识节点,也可以通过发表评论等方式为共享知识库增加新的知识

课后可以通过点击某一个知识节点进行复习,还可以查看与此主题相关的其他知识。

PS:只看见知识,看不见人,即学习过程中学习者通过发表评论,增加知识来表示自己的社区存在。

-

社会知识网络

-

网络技术与学习支持

活动类型:讨论交流活动名称:网络技术与学习支持活动描述:假设你是某大学二年级的学生,正在学习教育技术新发展这门课程,这门课程的主要特色为混合学习,即线上线下混合学习方式进行。现在基于平台界面除过学习内容和学习活动显示外,你可以选择一种学习网络辅助学习,那么你会选择那种?为什么?结合本节内容论述,包括分析其对学习的支持与你的需求等。-

Toward a Theory of Online Learning

The Web offers a host of very powerful affordances to educators. Existing and older education provisions have been defined by the techniques and tools designed to overcome the limitations and exploit the capacities of earlier media. For example, the earliest universities were constructed around medieval libraries that afforded access to rare hand-written books and manuscripts. Early forms of distance education were constructed using text and the delayed forms of asynchronous communications afforded by mail services. Campus-based education systems are constructed around physical buildings that afford meeting and lecture spaces for teachers and groups of students. The Web provides nearly ubiquitous access to quantities of content that are many orders of magnitude larger than those provided in any other medium.

From our earlier discussion, we see that the Web affords a vast potential for education delivery that generally subsumes almost all the modes and means of education delivery previously used, with perhaps the exception of the rich face-to-face interaction of the classroom. We have also seen that the most critical component of formal education consists of interaction between and among multiple actors, humans and agents included.

Thus, I conclude this chapter with an overview of a theory of online learning interaction that suggests that the various forms of student interaction can be substituted for each other, depending on costs, content, learning objectives, convenience, technology, and available time. The substitutions do not result in decreases in the quality of the learning that results. More formally. Sufficient levels of deep and meaningful learning can be developed, as long as one of the three forms of interaction (student-teacher; student-student; student-content) is at very high levels. The other two may be offered at minimal levels or even eliminated without degrading the educational experience. (Anderson, 2002).

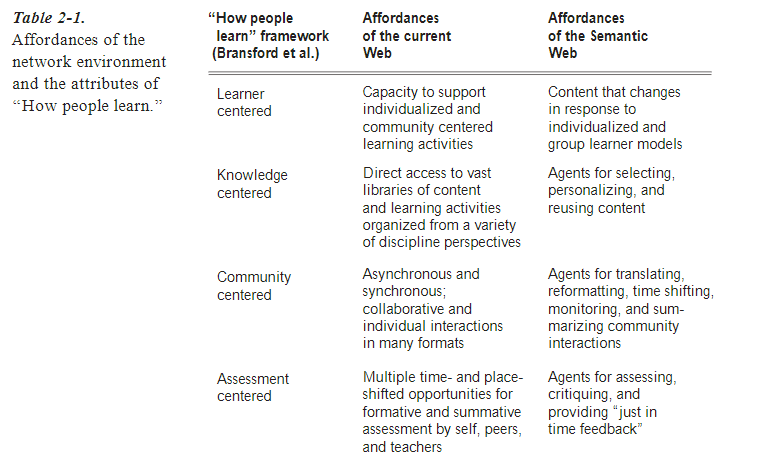

The challenge for teachers and course developers working in an online learning context is to construct a learning environment that is simultaneously learning centered, content centered, community centered, and assessment centered. There is no single, right medium of online learning, nor a formulaic specification that dictates the kind of interaction most conducive to learning in all domains with all learners. Rather, teachers must learn to develop their skills so that they can respond to student and curriculum needs by developing a set of online learning activities that are adaptable to diverse student needs. Table 2-1 illustrates how the affordances of these emerging technologies can be directed so as to create the environment that is most supportive of “how people learn.”

-

Conclusion

This discussion highlights the wide and diverse forms of teaching and learning that can be supported on the Web today, and the realization that the educational Semantic Web will further enhance the possibilities and affordances of the Web, making it premature to define a particular theory of online learning. However, we can expect that online learning, like all forms of quality learning, will be knowledge, community, assessment, and learner centered. Online learning will enhance the critical function of interaction in education in multiple formats and styles among all the participants.

These interactions will be supported by autonomous agents working on behalf of all participants. The task of the online course designer and teacher is to choose, adapt, and perfect (through feedback, assessment, and reflection) educational activities that maximize the affordances of the Web. In doing so, they create learning-, knowledge-, assessment-, and community-centered educational experiences that result in high levels of learning by all participants. Integration of the new tools and affordances of the Semantic Web further enhances the quality, accessibility, andd affordability of online learning experiences.

Our challenge as theory builders and online practitioners is to delineate which modes, methods, activities, and actors are most effective, in terms of cost and learning, in creating and distributing quality e-learning programs. The creation of a model is often the first step toward the development of a theory. The model presented illustrates most of the key variables that interact to create online educational experiences and contexts. The next step is to theorize and measure the direction and magnitude of the effect of each of these variables on relevant outcome variables, including learning, cost, completion, and satisfaction. The models presented in this chapter and other chapters in this book do not yet constitute a theory of online learning, but it is hoped that they will help us to deepen our understanding of this complex educational context and lead us to hypotheses, predictions, and most importantly improvements in our professional practice. It is hoped that the model and discussion in this and other chapters in this book lead us toward a theory of online learning.

-

拓展阅读

1.国际视野中的在线交互与网络分析:/public/2022/3/c77b82cc-f762-4a67-b9c7-a733637cf21b.pdf

2.基于交互主题的在线学习知识创造研究:/public/2022/3/f64d2a32-ee0b-418d-96ed-ae30b7016b8f.pdf

3.群体知识图谱建构对在线学习交互的影响研究:/public/2022/3/45b99281-07d4-4635-8507-a0a0413e6c06.pdf

4.在线同步教学中交互的设计与实施:/public/2022/3/d49373e8-cb26-4465-8f6f-79b3c3d7fe04.pdf

5. 在线学习的核心要义与转型路向:/public/2022/3/a5552d0a-bfb6-4b97-82a7-8a76ec7b25fe.pdf

-

说说你对本节学习内容的理解

-

分享与本节内容密切相关的最新研究成果

-

-

- 标签:

-

加入的知识群:

.jpg)

学习元评论 (0条)

聪明如你,不妨在这 发表你的看法与心得 ~